Changing trade flows threaten Middle East food security

By Chris Lyddon

A growing population and a limited supply of agricultural land and water means the Middle East countries must import grain, in a market that has changed dramatically in recent years, to feed their populations.

A series of crises has convinced governments that they need to ensure food security by holding stocks and buying grain well in advance.

Istanbul, Turkey-based Vural Kural, executive secretary of the International Association of Operative Millers’ Eurasia District, told World Grain at the International Grains Council (IGC) conference in London, England, that “over the last two decades, grain trade flows have significantly shifted, driven by price competitiveness, proximity to demand markets, political alignment, and infrastructure development.”

He highlighted the rise of the Black Sea region, largely displacing the United States, Canada and European Union suppliers.

“These countries have grown competitive due to lower production and transportation costs, strategic proximity to importers (MENA, Eastern Mediterranean, Asia), increasing investment in port and logistics infrastructure (e.g., Novorossiysk, Mykolaiv, Constanța),” Kural said. “This eastward shift in supply routes has made the Black Sea a central grain corridor, which is particularly significant for Turkey — positioned as a transit, processing and export hub.”

Kural explained that 25 years ago, in September 1999, Russia harvested 60 million tonnes of grain, up from the previous year’s disastrous 47.8 million.

“The United States shipped $1 billion of US corn, wheat, rice, pork, beef and dry milk to Russia under a food aid agreement,” he said. “Today, the Russian Federation is the world’s grain export leader with a grain export capacity of 80 million tonnes.

“The Black Sea is now the primary supply source for much of the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia, supplanting more distant suppliers. Turkey has emerged not just as an importer, but as the world’s leading flour exporter, by adapting to and leading within these new trade flows.”

Turkey went from relying on domestic grain production, with some imports from the EU and the United States, to over the past decade “a marked shift toward sourcing from Russia and Ukraine, due to geographic proximity, logistical advantages, and attractive pricing,” he said.

“Today Turkey imports grain, primarily wheat, from the Black Sea (Russia in particular), processes it into flour, and then exports flour to over 100 countries, making it the world’s leading flour exporter,” he said.

The eastern Mediterranean countries — Lebanon, Jordan and Syria — have “increased imports from Russia and Turkey due to pricing and logistics,” he said, while in Arab countries, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Yemen, “Russia and Ukraine now dominate wheat supply chains, especially for Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer.”

Iran is aiming for self-sufficiency, he said, but “recurrent droughts and trade limitations have led to greater imports from Kazakhstan and Russia.”

Looking to the future, he predicted that climate and geopolitics will have an increasing influence on trade flows, with climate change “affecting yields, shifting production zones, and creating new logistical bottlenecks.”

“Conflicts and sanctions — as seen in the Russia-Ukraine war — will reshape corridors and push diversification,” Kural said.

He also pointed to a trend toward regionalization. Countries will prioritize resilience and local storage over just-in-time efficiency, he said.

“Turkey’s role in the global grain and flour trade is underpinned by structural advantages, strategic foresight, and public-private coordination,” he said. “In an era defined by climate volatility, conflict-driven corridor shifts, food security tensions, and sustainability imperatives, Turkey stands out as a stable, capable, and competitive leader in flour trade.

“Turkey’s leadership will be tested by climate change, trade disruptions, and shifting consumption patterns, but its central location, developed infrastructure, and responsive policy environment provide strong foundations for continued influence and agility in the evolving grain economy.”

Potential trade diversion

At the recent IGC Conference in June, World Grain asked Middle East experts about the potential for trade diversion, particularly as the EU has ended the “Autonomous Trade Measures” under which Ukrainian grain could enter it freely.

Jordanian trader Malak Al Akiely, founder and chief executive officer of Golden Wheat for Grain Trading, stressed that from a Jordanian perspective, as well as in her work as the agent of other countries including Bahrain, “for the last five years we’ve been importing from Romania, and we buy specification. We don’t buy origin but because we are price sensitive.”

“For other buyers we import from Argentina, France, depending on the season, and Ukraine, but I would say for a price-sensitive country you just follow the specification, and it happens to be Romania for wheat,” she said. “The whole definition of a trader has been redefined after all we’ve been going through. We cannot just be traders now.

“You have to be an agronomist, you have to be an economist, you have to be a political enthusiast to follow what’s happening, but you just follow the price.”

Some of the wheat coming through Romania, however, is Ukrainian as well, because of the Danube River links.

“The last shipment we had actually was a panamax, 60,000 tonnes,” she said. “That was 40,000 from Romania and 20,000 from Ukraine.”

Al Akiely also explained how the attitude of governments in the region has changed, starting with the Russian export ban of 2008.

“It showed our government they had a new role,” she said, which meant “redefining what does it mean for them, food security?”

It took “political will and leadership,” which led to Jordan putting in place “a mandate to have a strategic reserve, minimum for six months.”

The system proved its worth during the pandemic, limiting the disruption to the supply chain.

She also pointed to investment in Aqaba, Jordan’s only port on the Red Sea.

“Just recently, we decided that Aqaba is going to be a world-class destination for investment in logistics,” she said. “So, with Abu Dhabi ports, also Aqaba Development Corporation, they founded a joint venture company, which is called Maqta Ayla.”

Al Akiely sits on the board of that company.

“The mandate of this company is to digitalize the port operation and be responsible for all the movement and streamline the flow of movement between trucks,” she said. “We’re talking about trucks moving commodities, around 4,000 trucks per day,” she said, noting that “30% of the world’s food waste is in storage and process handling.”

Mutlaq Al-Zayed, CEO of Kuwait Flour Mills and Bakeries, said Kuwait, which imports all its wheat, depends on storage.

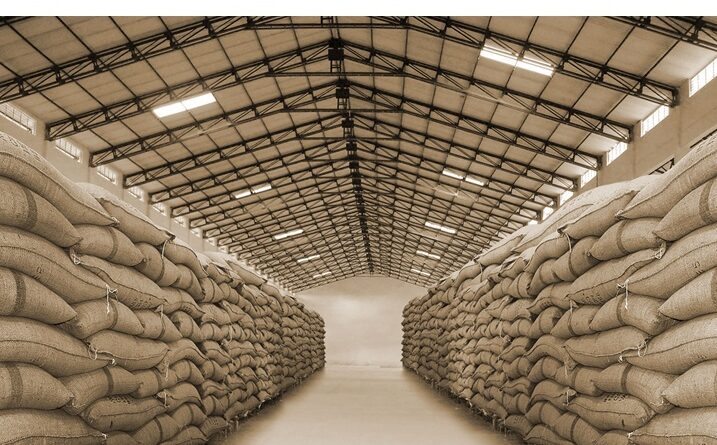

“We think that the storage is that is the father of food security because without storing, it will be difficult to meet the requirement of the people, and also the forward purchasing is very important,” he said. “We have as storage about three months to six months and forward purchasing for about six months.”

Kuwait had been through “maybe more crises than Jordan, especially in 1990 (with) the invasion, then the liberation of Iraq and after that in 2008 the economic crisis,” he said. “Then we had COVID and the Ukraine War. That’s all because of the storage and forward purchase.”

He also underlined the need to invest in manufacturing capacity as well as storage and trading infrastructure.

“Investment in factories, in manufacturers is very important,” he said.

“It’s very important to have the commercial expansion in our business so we also try to export around the GCC area,” he said, referring to the Gulf Cooperation Council, made up of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

“We concentrate on high quality and a fair price in that, and we are doing that very successfully,” he said. “It’s very important to have more innovative products. We have all kind of mixes of flour and also we have a feed mill.”

Vulnerable to supply disruptions

Tarek El Azab, commercial leader North Africa/Middle East of Corteva Agriscience, pointed out that “the region has experienced rapid population growth, exceeding 2%, which is actually higher than the average of the middle-income countries, 1.3%,” also explaining that land and water availability is limited.

“The biggest challenge is the import dependence,” he said. “The region is highly dependent on grain imports due to limited local production.”

“Include the global regulatory challenges like tariffs, stricter quality control, customs delays… add in geopolitical risks and currency controls, you will find that this import reliance makes the region vulnerable to global supply disruptions,” he said. “If we look at climatic change and environmental change, it’s actually adding more pressure to the local grain production.”

He called for better regulatory frameworks for regulating seed technology and also complained of “infrastructure and storage limitations as well.”

“So many countries in the region lack modern grain storage and logistics,” he said. Another problem was “regulatory fragmentation … countries with different local regulations, with different documentation.”He added, “Addressing the challenges in the grain industry in the Middle East requires a combination of policy reforms, technological innovation and regional cooperation, infrastructure investment as well.”

This article has been republished from The World Grain.